Venerating the past in itself will not solve the world’s problems. We need to find the link between our traditions and our present experience of life. Nowness, or the magic of the present moment, is what joins the wisdom of the past with the present. When you appreciate a painting or a piece of music or a work of literature, no matter when it was created, you appreciate it now. You experience the same now in which it was created. It is always now.

[CHÖGYAM TRUNGPA Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior]

Preamble:

At some point an Appendix will be put together providing more in-depth source materials for those interested, but for now we will continue with the author’s rudimentary babblings based on his training decades ago in such rather rare, pre-modern esoterica transported, most improbably, by a young Tibetan lama who escaped the communist invasion of his decidedly medieval Tibet by walking on foot for about a year, almost to the point of starvation, into India and from thence into the wider world of the twentieth century.

===========================================================

Like the Torii Gate shown in Introduction Part Two, the origins of the Heaven, Earth and Man formulation are shrouded in the mists of Time. The Swiss Alps mountain man, Otzi, discovered a while back frozen in a glacier for approximately five thousand years, carried not only a few ancient stone acupuncture needles but also several small, circular tattoos on various points in his legs where, to this day, practitioners needle to alleviate arthritis, which he clearly had. The fact that this man had both acupuncture needles and marked points in Europe around 2,500 BC demonstrates how little we know of our own relatively recent history; in any case, where there was acupuncture there was almost certainly some sort of yin-yang theory and therefore also some notion of Heaven Earth and Man, given that Heaven and Earth are in many ways the primordial Yang and Yin formulations. So this is a very ancient trinitarian formulation, quite possibly the oldest of all, especially given how it needs no religious dogma or belief system to appreciate.

‘Ok’, you might say, ‘it’s old; so what?’ Well, let us explore. First I shall provide a traditional academic definition, then something from a contemporary teacher, and finally will unpack it a little further myself. Part of the reason I like to offer the first type of excerpt is that it’s a personal mission, of sorts, to show that many things seemingly frozen in time within formulaic academic language are still very much alive and kicking, though not readily apparent in today’s society. They echo the wittily portrayed god Pan in Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume: because no-one believes in him, nor any of the old Gods, any more he has faded from view, so all that remains is a horribly pungent odour wafting by in the wake of his invisible passage causing people to twicht or spasm in disgust, though they know not why!

Heaven and Man Are United as One.

The term represents a world outlook and a way of thinking which hold that heaven and earth and man are interconnected. This world outlook emphasizes the integration and inherent relationship between heaven, earth, and man. It highlights the fundamental significance of nature to man or human affairs, and describes the endeavour made by man to pursue life, order, and values through interaction with nature. The term has different ways of expression in history, such as heaven and man are of the same category, sharing the same vital energy, or sharing the same principles. Mencius(372?-289 BC), for one, believed that through mental reflection one could gain understanding of human nature and heaven, emphasizing the unity of mind, human nature, and heaven. Confucian scholars of the Song Dynasty sought to connect the principles of heaven, human nature, and the human mind. Laozi maintained that “man’s law is earthly, earth’s law is natural, and heaven’s law is Dao.” Depending on a different understanding of heaven and man, the term may have different meanings.

CITATION 1

In terms of integration of categories, heaven and man are one. (Dong Zhongshu: Luxuriant Gems of The Spring and Autumn Annals)

CITATION 2

A Confucian scholar is sincere because of his understanding, and he achieves understanding because of his sincerity. That is why heaven and man are united as one. One can become a sage through studies, and master heaven’s law without losing understanding of man’s law. (Zhang Zai: Enlightenment Through Confucian Teachings)

======================================================================

Now the more contemporary excerpt by my teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoché from a lecture given in 1979 introducing this triad in the context of a Dharma Arts Seminar wherein the Arts are viewed as a vehicle for spreading wakefulness in society, enlightened culture as it were. [Emphasis mine]

2. CREATION

“Being an artist is not an occupation; it is your life, your whole being.”

The principle of heaven, earth, and man seems to be basic to a work of art. Although this principle has the ring of visual art, it also could be applied to auditory art such as poetry or music, as well as to physical or three-dimensional art. The principle of heaven, earth, and man applies to calligraphy, painting, interior decoration, building a city, creating heaven and earth, designing an airplane or an ocean liner, organizing the dish washing by choosing which dish to wash first, or vacuuming the floor. All of those works of art are included completely in the principle of heaven, earth, and man.

The heaven, earth, and man principle comes from the Chinese tradition, and it was developed further in Japan. Currently the phrase “heaven, earth, and man” is very much connected with the tradition of ikebana, or Japanese flower arranging, but we should not restrict it to that. If you study the architectural vision of a place such as Nalanda University in India, or if you visit Bodhgaya, with its stupa and its compound, or the Buddhist and Hindu temple structures of Indonesia, you see that they are all founded on the heaven, earth, and man principle. This principle is also seen in the interior decor of temples built in medieval times and occupied by a group of practitioners: monks, deities, lay students, and their teacher. The principle of heaven, earth, and man is also reflected in the makeup of the imperial courts of China, Japan, and Korea, and in their official hierarchy, which included an emperor, empress, ministers, subjects, and so forth. In horseback riding, the rider, the horse, and his performance are connected with the heaven, earth, and man principle, which also applies to archery and swordsmanship.

Anything we do, traditionally speaking, whether it is Occidental or Oriental, contains the basic principle of heaven, earth, and man. At this point we are talking about the heaven, earth, and man principle from the artist’s point of view rather than the audience’s.

In the concept of heaven, earth, and man, the first aspect is heaven. The heaven principle is connected with non thought, or vision. The idea of heaven is like being provided with a big canvas, with all the oil paints, and a good brush. You have an easel in front of you, and you have your smock on, ready to paint. At that point you become frightened, you want to chicken out, and you do not know what to do. You might think, “Maybe I should skip the whole thing, have a few more coffees or something.” You might have blank sheets of paper and a pen sitting on your desk, and you are about to write poetry. You begin to pick up your pen with a deep sigh—you have nothing to say. You pick up your instrument and do not know what note to play. That first space is heaven, and it is the best one. It is not regarded as regression, particularly; it is just basic space in which you have no idea what it is going to do or what you are going to do about it or put into it. This initial fear of inadequacy may be regarded as heaven, basic space, complete space. Such fear of knowledge is not all that big a fear, but a gap in space that allows you to step back. It is one’s first insight, a kind of positive bewilderment.

Then, as you look at your canvas or your notepad, you come up with a first thought of some kind, which you timidly try out. You begin to mix your paints with your brush, or to scribble timidly on your notepad. The slogan “First thought is best thought!” is an expression of that second principle, which is earth.

The third principle is called man. The man principle confirms the original panic of the heaven principle and the “first thought best thought” of the earth principle put together. You begin to realize that you have something concrete to present. At that point there is a sense of joy and a slight smile at the corners of your mouth, a slight sense of humour. You can actually say something about what you are trying to create. That is the third principle, man.

So we have heaven, earth, and man. To have all three principles, first you have to have the sky; then you have to have earth to complement the sky; and having sky and earth already, you have to have somebody to occupy that space, which is man. It is like creation, or genesis. This principle of heaven, earth, and man is connected with the ideal form of a work of art, although it includes much more than that. And, to review, all of what we have discussed so far is based on the ground of health, on the idea of complete coolness, and a general sense of sanity. [Chögyam Trungpa, Collected Works, Volume 7]

First, notice the difference between the two excerpts. Here we see how seemingly distant abstract concepts can be brought to life by someone actually living the principles in the here and now. Trungpa Rinpoché explains the terms from the point of view of an artist and spiritual teacher practicing them in everyday life.

But let us start at the beginning, which is especially appropriate because in a way the Heaven Earth & Man triad, as per the above excerpt’s title, in a way describe Creation, which of course is a continuously ongoing process taking place in the present moment. Again:

“To have all three principles, first you have to have the sky; then you have to have earth to complement the sky; and having sky and earth already, you have to have somebody to occupy that space, which is man. It is like creation, or genesis.”

If we look out the window or walk outside, immediately we are struck with the over-arching presence of the sky above; this is nothing mystical, per se, rather immediate and direct. Then we can also observe the earth below and around with its endless variegations and multiplicities – all forms appearing under the essentially formless sky. Each tree has no end of leaves, each animal no end of hairs, each garden path no end of little pebbles, flowers, blades of grass and so forth. And here we are walking in between such Heaven and Earth as indeed we do throughout our lives, always. Now the artist’s perspective Trungpa Rinpoché provides adds a layer which helps us understand the experiential nature of this triad, but our concern again, at this stage, is not so much trying to slot this into any spiritual journey or practice, rather just to grasp the basic concept as part of our initial layers & levels skandha-gathering process.

That said, it is very helpful to take the above descriptions, especially Trungpa’s, and observe them at play in everyday life. This can be in small or large situations, for example how objects are arranged on the dining table, or how everything is put together in the kitchen, living room or bedrooms; or in public spaces how streets are laid out, which churches have a strong sense of sacred presence and which do not, which buildings express civilizational dignity and which are ‘off’ somehow.

Or one could analyze corporate or national governance along those lines as well, not to mention movies, sports events, political gatherings or military campaigns. Some organizations have a great sense of Heaven but lack connection with Earth, others the reverse; in the former those involved (Man) will tend to be overly ideological, perhaps unable to implement what they envisage, whereas in the latter they may overly fixate on the best manufacturing methods whilst avoiding discussions of overall vision, design and organizational viability.

Literally speaking, every house, for example, has a roof, without which it would not be one. The roof clearly connects with the sky above but also from within is the sky of the house inside. Roofs have qualities determined by quality of materials, dimensions, shape, whether or not they provide shade below with covered porches or not, whether they provide a sense of space inside or are oppressive, and so on. Then the Earth aspect is not only how the house sits on the ground and is positioned relative to the terrain and neighbouring houses, but again the materials, the quality of workmanship of the floor, walls, furniture – the gestalt of the physical structure including its plumbing, electrical and heating systems. The Man principle may have more to do with the overall feel and flow, for example where the kitchen is placed relative to the entrance, how the view for the person washing the dishes looks out onto a lovely flower garden or ugly brick wall. Also what sort of family lives there: are they social, talking and laughing a lot, or is it the house of a recluse, or a murderer, or political conspirators, or a family of quarrelling alcoholics.

A key aspect of this triad is the notion of Heaven itself. In Chinese philosophical circles there are long-standing arguments about absolute higher pristine Heaven versus relative lower mundane heaven – both Citations in the first excerpt were about this, for example. But what really matters is for these principles to come to life, to which end what is absolutely (pun intended) required is some sort of sacred outlook. Both Iain McGilchrist and Alexander Dugin have rightly stressed this as a sine qua non of good lives and society; moreover it is an experiential value increasingly alien to modernist, secular materialists – nearly everyone these days. In a way, this sense of sacredness IS the Heaven principle, atmospherically speaking, and of course as with everything there are different layers and levels of experiencing it, so no need for extended academic arguments. Also, although the Christian West’s notion of Heaven has certain overlap with this older, less faith-based formulation, this triad concerns here-and-now perception and experience, not anything other-worldly or afterlife related.

The sky presides over everything, is always there no matter what takes place. This ever-present nowness contains aspects of sacredness already; just as the profound majesty and limitlessness of Nature, the Earth principle, is another sacred aspect as well along with Nature’s inherent beauty, which all naturally appreciate.

Sacred art displays and engenders this, moreover all sacred perception comes from the experiencer being between the uplifting embrace of timeless, all-encompassing, absolute level Heaven and limitlessly variegated relative level Earth, both of which are fundamentally and primordially sacred, the experience of which quality is Man. In the West, cathedrals were a sacred art form dedicated to exploring these principles and making them part of both national and community cultural life.

Nowness is an inner, experiential aspect of the ever-present, all-pervasive Heaven principle. Another major aspect of this triad is that it both assumes and frames some sort of natural Order, or hierarchy. Things have their place just as with Heaven above and Earth below. The Man principle can be well or poorly executed thus societies can be well or poorly attuned to Heaven resulting in a discombobulated Man who cannot manage the practicalities of Earth and ends up creating a mess, either at the individual, family, community or national level. As you can see, this triad has broad implications and though not often mentioned in today’s post-industrial revolution Asia, it pervades much of their thinking and to this day deeply influences their view. Indeed, we can say It has likely been absorbed into their genetic makeup, as with all great civilizational ideas. Again:

Venerating the past in itself will not solve the world’s problems. We need to find the link between our traditions and our present experience of life. Nowness, or the magic of the present moment, is what joins the wisdom of the past with the present. When you appreciate a painting or a piece of music or a work of literature, no matter when it was created, you appreciate it now. You experience the same now in which it was created. It is always now.

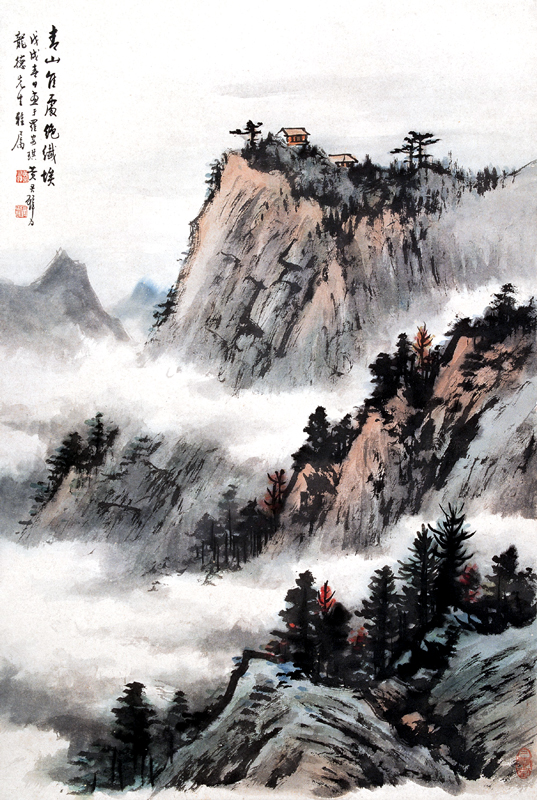

Here follow two more paintings by the same artist. Notice how in all three there is, however small and dwarfed by the majesty of Heaven and Earth, a Man principle. Note also how in the first Man is placed where he traditionally belongs, in the Middle, whereas in the second he is at the bottom and in the third he is at the top.

and last but not least:

In the last two, the artist is playing around with where to put the Man principle; in the first it is very small and low down in the river valley, barely noticeable; in the second it is also quite small but on top of a dramatic mountain formation. Notice also how in the last one the orange colour in the house on top is echoed on the top of each lower mountain formation with the same orange splotches on one or two of the trees – a sort of mini-Man principle echoing the main Man principle expression of the two houses on top with windows placed overlooking the terrain below giving the sense of a witnessing mind, which is the animating Man principle. Note also how three paintings feature so many different layers and levels and in the last one there are three main levels, each with its own Heaven and Earth composition, again making those orange splotches on top the Man principle.

There are schools of art, especially flower arranging schools in Japan, which train students for years in how to perceive and then artistically heighten awareness of this triad. It is deeply woven into the fabric of all major Asian civilizations and of course exists also in the West, though not formulated as such.

Let us end with a haiku based on the last painting using a haiku technique from Trungpa’s Shambhala tradition which considers the first line a type of Heaven, then the second line a type of Earth complementing that first line, then the last line is Man, animating or tying the whole thing together somehow, usually with some sort of human feeling.

gazing down from on high

at swirling mist and mountains below

such quietly breathing splendour!

[Editor’s Note: at over 3,100 words, this is longer than desired, but since it includes over 1200 words from excerpts, the author’s contribution is around 2,000 words which is within the intended parameters.]

2 thoughts on “Layers & Levels Chapter Five: Heaven Earth & Man”